Unpredictable as Weather (Part 5)

It is said that everyone complains about the weather, but no one does anything about it. Not so of our toons, for, as will be seen, at least two of them in today’s survey take matters into their own hands, to make a distinct change in the climate. We’ll visit with others whose encounters with the forces of nature range from mere mood atmospherics to rampaging storms – including a Technicolor visit with our old friend, Noah.

The Wizard of Oz (Ted Eshbaugh, unreleased), has been visited many times in these columns, and will not be elaborated upon here, beyond mentioning its mere four shots of twister action, filmed in black and white in the same manner as MGM’s later feature classic. The animation of the twister is competent, but not spectacular, seeming rather hurried to accommodate the time constraints of telling a tale in seven or so minutes flat. There is no spectacle of odd and unusual passing objects in the storm, nor does the house fall on any wicked witch. Quite honestly, Fleischer’s Tree Saps did it much better, and considerably more dramatically.

The Wolf At the Door (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 12/29/32, Dick Huemor, dir.) – A favorite from the Scrappy catalogue. It is essentially “Big Man From the North”, taken one better, with stronger gags, more lineal plotting, and no side trips for musical interludes. An old goat in a remote cabin is being terrorized by the howls and attempts to gain entry of a timber wolf. He places a call to the local mounted police. Chief Scrappy sends Officer Oopie to bring in the wolf, whose wanted poster hangs on the wall, dead or alive. But, as in Bosko’s earlier mission, there is a raging blizzard going on outside. An unbolting of the heavy wooden door of the station lets in a gale force wind laden with snow, blowing Oopie back against the opposite wall, and dislodging a shelf above him, with its contents, consisting of a row of plates, striking Oopie on the head one by one. Scrappy arms Oopie with full-regulation crime-fighting apparatus (a butterfly net), sets him at the door, and orders him forward. Oopie bravely launches into the snow, while Scrappy struggles against the wind to close and re-bolt the door. Scrappy grabs a spyglass, and peers out a window to monitor Oopie’s progress – but hears a knock at the door. Opening it, he finds Oopie – not only back, but frozen stiff in a coating of ice. Scrappy brings his popsicle partner inside, and shakes him loose from the ice coat. Scrappy then runs to a pot-bellied stove, on which is brewing a kettle of hot water. He pours the contents of the kettle into a hot water bottle, then ties the bottle onto Oopie’s head in place of his mountie hat. Oopie charges out the door again – but Scrappy has barely bolted the door when there is a knock again. Oopie is back, not frozen, but still trembling with cold. He whispers a request to Scrappy. Scrappy responds, returning with a second hot water bottle, which he slips under Oopie’s nightshirt, and ties around the youth’s bare rear end. Oopie finally makes it out the door, and trudges against the winds to the goat’s cabin. The wolf is now not only at the door, but has sawed a hole through it, and has the goat in a stranglehold. Oopie turns the door handle to open it, ignoring the gaping hole already cut into it – except to reach his hand out the hole to retrieve the butterfly net he has left on the porch. “You’re under arrest”, he announces to the wolf, slipping the net under the wolf’s feet, and raising it so that the wolf wears the netting like a pair of short briefs. The wolf is unimpressed, and boots Oopie into the wall, where a wall phone crashes down upon him. Oopie makes a call for help of his own, back to Scrappy at headquarters. Never send a baby to do a boy’s job. Scrappy runs to a log cabin hangar, and pilots a small plane to the crime scene. He detaches the machine gun from his plane, mounting it on the ground. Then, he climbs a ladder to the roof edge of the cabin, and breaks off a long string of icicles hanging from the roof eaves. Feeding the icicle strip into his machine gin, Scrappy uses it as an ammunition belt, peppering the wolf with the pointed ends of the icicles. Oopie joins the battle, by laying the goat on the ground, filling his cheeks with snowballs, then using him as a batting machine to launch each ball out of his mouth when his stomach is stepped on, allowing Oopie to whack each ball with a baseball bat. The barrage puts the wolf on the run. The wolf is left howling on a hilltop, while the smoke from the chimney of the log cabin forms the outline of a hand giving him a deriding nose-wave, for the iris out.

The Wolf At the Door (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 12/29/32, Dick Huemor, dir.) – A favorite from the Scrappy catalogue. It is essentially “Big Man From the North”, taken one better, with stronger gags, more lineal plotting, and no side trips for musical interludes. An old goat in a remote cabin is being terrorized by the howls and attempts to gain entry of a timber wolf. He places a call to the local mounted police. Chief Scrappy sends Officer Oopie to bring in the wolf, whose wanted poster hangs on the wall, dead or alive. But, as in Bosko’s earlier mission, there is a raging blizzard going on outside. An unbolting of the heavy wooden door of the station lets in a gale force wind laden with snow, blowing Oopie back against the opposite wall, and dislodging a shelf above him, with its contents, consisting of a row of plates, striking Oopie on the head one by one. Scrappy arms Oopie with full-regulation crime-fighting apparatus (a butterfly net), sets him at the door, and orders him forward. Oopie bravely launches into the snow, while Scrappy struggles against the wind to close and re-bolt the door. Scrappy grabs a spyglass, and peers out a window to monitor Oopie’s progress – but hears a knock at the door. Opening it, he finds Oopie – not only back, but frozen stiff in a coating of ice. Scrappy brings his popsicle partner inside, and shakes him loose from the ice coat. Scrappy then runs to a pot-bellied stove, on which is brewing a kettle of hot water. He pours the contents of the kettle into a hot water bottle, then ties the bottle onto Oopie’s head in place of his mountie hat. Oopie charges out the door again – but Scrappy has barely bolted the door when there is a knock again. Oopie is back, not frozen, but still trembling with cold. He whispers a request to Scrappy. Scrappy responds, returning with a second hot water bottle, which he slips under Oopie’s nightshirt, and ties around the youth’s bare rear end. Oopie finally makes it out the door, and trudges against the winds to the goat’s cabin. The wolf is now not only at the door, but has sawed a hole through it, and has the goat in a stranglehold. Oopie turns the door handle to open it, ignoring the gaping hole already cut into it – except to reach his hand out the hole to retrieve the butterfly net he has left on the porch. “You’re under arrest”, he announces to the wolf, slipping the net under the wolf’s feet, and raising it so that the wolf wears the netting like a pair of short briefs. The wolf is unimpressed, and boots Oopie into the wall, where a wall phone crashes down upon him. Oopie makes a call for help of his own, back to Scrappy at headquarters. Never send a baby to do a boy’s job. Scrappy runs to a log cabin hangar, and pilots a small plane to the crime scene. He detaches the machine gun from his plane, mounting it on the ground. Then, he climbs a ladder to the roof edge of the cabin, and breaks off a long string of icicles hanging from the roof eaves. Feeding the icicle strip into his machine gin, Scrappy uses it as an ammunition belt, peppering the wolf with the pointed ends of the icicles. Oopie joins the battle, by laying the goat on the ground, filling his cheeks with snowballs, then using him as a batting machine to launch each ball out of his mouth when his stomach is stepped on, allowing Oopie to whack each ball with a baseball bat. The barrage puts the wolf on the run. The wolf is left howling on a hilltop, while the smoke from the chimney of the log cabin forms the outline of a hand giving him a deriding nose-wave, for the iris out.

The Mad Doctor (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 1/21/33 – David Hand, dir.) – An unusual and memorable Gothic installment of the Mickey series, which was the only Mickey to earn an “A” (adult) rating from the British Board of Film Censors. The film plays on the recent success of Warner Brothers’ “Doctor X”, introducing us to a mad scientist, Dr. XXX. It opens on a traditionally dark and stormy night, with Pluto out in the yard, tied to his doghouse, and howling at the moon. Mickey, in his own bedroom, attempts sleep between shattering bolts of lightning seen through his window. Suddenly, a blood-curdling howl is heard from Pluto, as well as the cackle of fiendish laughter. Mickey is startled awake, and, in a tremulous voice, calls for Pluto. Another lightning bolt shatters the air. “PLUTO!”, he shouts. Outside, amidst blasts of wind and passing flurries of fallen leaves, a hooded figure drags Pluto by the leash, out of the yard and into a dark forest, the dog struggling against the rope to no avail. Mickey leaps out the window into the yard just as the hooded culprit disappears. Mickey finds the rope end severed where Pluto was tied, and the dog gone – but a trail of footprints provides a clue to follow to track his best friend. More lightning and rain flashes to light the terrain intermittently, as the shadowy figure drags Pluto across a long wooden drawbridge, to a spiked castle portcullis, which opens at the hooded figure’s pull of a lever to admit himself and Pluto inside, then closes with a slam behind him. Mickey arrives, slowly crossing the drawbridge to the door. As he walks, each board of the drawbridge falls away behind him into a deep moat, until Mickey finds himself standing on a narrow ledge before the door, with no way back. To keep his balance, Mickey grabs onto the handle of a brass door knocker shaped like a lion’s head. The head opens its mouth, then sucks in its own handle, dragging Mickey through the door and inside.

The Mad Doctor (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 1/21/33 – David Hand, dir.) – An unusual and memorable Gothic installment of the Mickey series, which was the only Mickey to earn an “A” (adult) rating from the British Board of Film Censors. The film plays on the recent success of Warner Brothers’ “Doctor X”, introducing us to a mad scientist, Dr. XXX. It opens on a traditionally dark and stormy night, with Pluto out in the yard, tied to his doghouse, and howling at the moon. Mickey, in his own bedroom, attempts sleep between shattering bolts of lightning seen through his window. Suddenly, a blood-curdling howl is heard from Pluto, as well as the cackle of fiendish laughter. Mickey is startled awake, and, in a tremulous voice, calls for Pluto. Another lightning bolt shatters the air. “PLUTO!”, he shouts. Outside, amidst blasts of wind and passing flurries of fallen leaves, a hooded figure drags Pluto by the leash, out of the yard and into a dark forest, the dog struggling against the rope to no avail. Mickey leaps out the window into the yard just as the hooded culprit disappears. Mickey finds the rope end severed where Pluto was tied, and the dog gone – but a trail of footprints provides a clue to follow to track his best friend. More lightning and rain flashes to light the terrain intermittently, as the shadowy figure drags Pluto across a long wooden drawbridge, to a spiked castle portcullis, which opens at the hooded figure’s pull of a lever to admit himself and Pluto inside, then closes with a slam behind him. Mickey arrives, slowly crossing the drawbridge to the door. As he walks, each board of the drawbridge falls away behind him into a deep moat, until Mickey finds himself standing on a narrow ledge before the door, with no way back. To keep his balance, Mickey grabs onto the handle of a brass door knocker shaped like a lion’s head. The head opens its mouth, then sucks in its own handle, dragging Mickey through the door and inside.

The remainder of the action is indoors, as Mickey explores the spooky castle abode, full of staircases inhabited by skeletons, giant spiders, falling knives and cleavers, and the like. The Doctor meanwhile has Pluto tied up in the lab, planning to extricate some of the dog’s vital organs for a graft onto a chicken, to see if whatever hatches from its egg will bark or cackle. Mickey ultimately falls upon an operating table, with manacles that lock around him. At the pill of a lever, a buzz saw descends from the ceiling, aimed right at Mickey’s bare midriff. Mickey struggles to suck his stomach in, calling for help and for Pluto. The scene transforms back to Mickey’s bedroom, where it is all just a nightmare. Hearing his name called from the half-asleep Mickey, Pluto appears at the window, dragging in the doghouse he is still tied to, to lick his master a fond, “Good morning” for the iris out.

Is My Palm Read (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 2/17/33 – Dave Fleischer, dir., David Tendlar/William Henning, anim.), has been visited several times in these columns. It provides a second, but brief, opportunity for Betty to be involved in a shipwreck – although only within the confines of a prediction within a crystal ball by Professor Bimbo. At the first sign of rain, the three-stack ocean liner on which Betty is bound produces an arm, to hold up a huge umbrella over its head. The waves commence the usual treatment of the ship, their white caps forming into fists and socking the ship at stem and stern. Then, the two watery hands cooperatively grab both bow and stern of the ship, lift it out of the water, and turn it upside down, to dump all crew and passengers into the sea. As the passengers, seen only as small dots, float helplessly, the ship, now righted again, blows a few large smoke rings from its stacks, then pitches them with one of the stacks into the water, where they serve as huge life preservers to float the passengers away. With no other outward signs of damage or flooding, the ship arbitrarily decides to sink beneath the waves, as a sole dot remains visible on the water’s surface. The camera zooms into the crystal ball to reveal Betty, adrift on a small life preserver of her own (not merely made of smoke). She drifts to a tropical island, where the breaking surf can’t seem to “keep its hands to you”, affectionately patting Betty’s rear end. Betty changes out of her wet things long enough to be seen in her undies, then dons some local foliage as a grass skirt. Things get weirder as Betty is dragged into a hut by a flock of ghosts of various ethnicities (including one Jewish), and held prisoner by spider’s web bars at the windows. Bimbo writes himself into the prediction, as a shore-patrol sailor on horseback to the rescue, and helps Betty make an escape upon a small paddleboat powered by a squirrel atop a hamster wheel trying to reach a nut. The scene returns to the fortune-telling parlor, where, suddenly, without need for reprise of either the shipwreck or the kidnaping, the prediction begins coming true, with the ghosts emerging from the pedestal of the crystal ball, and ripping away Betty’s long dress, under which she just happens to be wearing her hula girl attire! The film abruptly ends with the chase still in full progress, and Bimbo repeatedly knocking ghosts out the end of a hollow log and over a cliff.

Is My Palm Read (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 2/17/33 – Dave Fleischer, dir., David Tendlar/William Henning, anim.), has been visited several times in these columns. It provides a second, but brief, opportunity for Betty to be involved in a shipwreck – although only within the confines of a prediction within a crystal ball by Professor Bimbo. At the first sign of rain, the three-stack ocean liner on which Betty is bound produces an arm, to hold up a huge umbrella over its head. The waves commence the usual treatment of the ship, their white caps forming into fists and socking the ship at stem and stern. Then, the two watery hands cooperatively grab both bow and stern of the ship, lift it out of the water, and turn it upside down, to dump all crew and passengers into the sea. As the passengers, seen only as small dots, float helplessly, the ship, now righted again, blows a few large smoke rings from its stacks, then pitches them with one of the stacks into the water, where they serve as huge life preservers to float the passengers away. With no other outward signs of damage or flooding, the ship arbitrarily decides to sink beneath the waves, as a sole dot remains visible on the water’s surface. The camera zooms into the crystal ball to reveal Betty, adrift on a small life preserver of her own (not merely made of smoke). She drifts to a tropical island, where the breaking surf can’t seem to “keep its hands to you”, affectionately patting Betty’s rear end. Betty changes out of her wet things long enough to be seen in her undies, then dons some local foliage as a grass skirt. Things get weirder as Betty is dragged into a hut by a flock of ghosts of various ethnicities (including one Jewish), and held prisoner by spider’s web bars at the windows. Bimbo writes himself into the prediction, as a shore-patrol sailor on horseback to the rescue, and helps Betty make an escape upon a small paddleboat powered by a squirrel atop a hamster wheel trying to reach a nut. The scene returns to the fortune-telling parlor, where, suddenly, without need for reprise of either the shipwreck or the kidnaping, the prediction begins coming true, with the ghosts emerging from the pedestal of the crystal ball, and ripping away Betty’s long dress, under which she just happens to be wearing her hula girl attire! The film abruptly ends with the chase still in full progress, and Bimbo repeatedly knocking ghosts out the end of a hollow log and over a cliff.

Happy Hoboes (Van Buren/Radio Pictures, Tom and Jerry, 3/31/33 – George Stallings/George Rufle, dir.) – And we think the homeless problem is something only of our generation! Tom and Jerry are the latest residents of a homeless encampment on the edge of town, where everyone lives in little portable box houses of their own creation. Jerry is at least courteous enough to be a neat freak, spending most of his time sweeping and dusting. Tom prefers to bow on a homemade bass fiddle comprised of two strings strung over the side of an open cardboard box, while Jerry adds flute cadenzas, in a chorus of “A Shanty in Old Shanty Town.” Mirroring events of the current day, an officer of the law arrives, posting a notice to the encampment residents: “All bums out of here by sundown.” Our heroes and the rest of the bums pick up their tumble-down shacks (one stacking on top of his roof an additional portable outhouse), and make for the local train yard. They clamber into box cars to search for greener pastures. Tom and Jerry stomp on the roof of their shanty before boarding, compressing it into compact form to fit neatly between the rods of the box car. (Continuity of this gag is quickly ignored, as a scene during their train travel shows Jerry opening a trap door in the box cae’s floor to do a little fishing – with no sign of the compressed shanty below to block his way.) Above, two black clouds slowly roll into camera view from either side of the screen, and bump in rolling motion, again and again and again. A view from the top reveals the clouds’ shape above to be in the form of twin beds, and resting in each one, a female angel. One is awakened, and in musical pantomime begins complaining to the other. The second, roused by the commotion, responds by tossing her pillow at the first angel, a few feathers flying from its casing. The first angel responds in kind, and soon, a furious pillow fight has erupted. The “feathers” take on the form of snowflakes, then snow flurries, and soon, the countryside below them is being blanketed with a thick coating of snow.

Happy Hoboes (Van Buren/Radio Pictures, Tom and Jerry, 3/31/33 – George Stallings/George Rufle, dir.) – And we think the homeless problem is something only of our generation! Tom and Jerry are the latest residents of a homeless encampment on the edge of town, where everyone lives in little portable box houses of their own creation. Jerry is at least courteous enough to be a neat freak, spending most of his time sweeping and dusting. Tom prefers to bow on a homemade bass fiddle comprised of two strings strung over the side of an open cardboard box, while Jerry adds flute cadenzas, in a chorus of “A Shanty in Old Shanty Town.” Mirroring events of the current day, an officer of the law arrives, posting a notice to the encampment residents: “All bums out of here by sundown.” Our heroes and the rest of the bums pick up their tumble-down shacks (one stacking on top of his roof an additional portable outhouse), and make for the local train yard. They clamber into box cars to search for greener pastures. Tom and Jerry stomp on the roof of their shanty before boarding, compressing it into compact form to fit neatly between the rods of the box car. (Continuity of this gag is quickly ignored, as a scene during their train travel shows Jerry opening a trap door in the box cae’s floor to do a little fishing – with no sign of the compressed shanty below to block his way.) Above, two black clouds slowly roll into camera view from either side of the screen, and bump in rolling motion, again and again and again. A view from the top reveals the clouds’ shape above to be in the form of twin beds, and resting in each one, a female angel. One is awakened, and in musical pantomime begins complaining to the other. The second, roused by the commotion, responds by tossing her pillow at the first angel, a few feathers flying from its casing. The first angel responds in kind, and soon, a furious pillow fight has erupted. The “feathers” take on the form of snowflakes, then snow flurries, and soon, the countryside below them is being blanketed with a thick coating of snow.

In a gag that would be lifted by James Culhane at Walter Lantz about a decade later, the train is completely buried in the blizzard, only its protruding smokestack marking the curving trail of the hidden tracks below. The train manages to forge its way into high timber country, where it emerges into view atop the snow, long enough for the train to sniff at tree trunks like a dog ready to mark its territory. This allows Tom, Jerry, the engineer, and the brakeman, a chance to get a whiff of the cook shed of the local lumber camp, where a Chinese cook has just set out a full table of roast chickens. The train chugs to the cook shed, and our heroes and the train personnel stare hungrily and with drooling tongues at the banquet. The lumber camp’s boss graciously calls out, “Come on, boys. Have something to eat.” He has not reckoned on the fact that this is also overheard by all the other hoboes in the box cars, who storm out of the train in a stampede, piling onto the chef’s platter to devour everything in sight. The lumber boss swears revenge, and pulls out the support pin from a huge pile of stacked logs. The logs roll like an avalanche, sweeping train, hoboes, shanties, and even the cook shed into the river below. Everyone drifts downstream on the swollen wave caused by the avalanche, with Tom and Jerry at the forefront. Then the waters subside, revealing land below them – the same vacant lot from which their journey started! Curiously, Tom and Jerry ignore the still-posted sign about their needing to get out by sundown, and emerge from their shanty with boxes to set a dinner table – followed by the Chinese cook with another fresh batch of roast chickens! The boys eat happily for the iris out, devil may care as to what comes their way next. Animation on this one is notable for being unusually smooth and fluid in motion, though fraught with errors in the inking and painting department, obviously not used to being consistent in the face of more-than-usually intensive effort.

In a gag that would be lifted by James Culhane at Walter Lantz about a decade later, the train is completely buried in the blizzard, only its protruding smokestack marking the curving trail of the hidden tracks below. The train manages to forge its way into high timber country, where it emerges into view atop the snow, long enough for the train to sniff at tree trunks like a dog ready to mark its territory. This allows Tom, Jerry, the engineer, and the brakeman, a chance to get a whiff of the cook shed of the local lumber camp, where a Chinese cook has just set out a full table of roast chickens. The train chugs to the cook shed, and our heroes and the train personnel stare hungrily and with drooling tongues at the banquet. The lumber camp’s boss graciously calls out, “Come on, boys. Have something to eat.” He has not reckoned on the fact that this is also overheard by all the other hoboes in the box cars, who storm out of the train in a stampede, piling onto the chef’s platter to devour everything in sight. The lumber boss swears revenge, and pulls out the support pin from a huge pile of stacked logs. The logs roll like an avalanche, sweeping train, hoboes, shanties, and even the cook shed into the river below. Everyone drifts downstream on the swollen wave caused by the avalanche, with Tom and Jerry at the forefront. Then the waters subside, revealing land below them – the same vacant lot from which their journey started! Curiously, Tom and Jerry ignore the still-posted sign about their needing to get out by sundown, and emerge from their shanty with boxes to set a dinner table – followed by the Chinese cook with another fresh batch of roast chickens! The boys eat happily for the iris out, devil may care as to what comes their way next. Animation on this one is notable for being unusually smooth and fluid in motion, though fraught with errors in the inking and painting department, obviously not used to being consistent in the face of more-than-usually intensive effort.

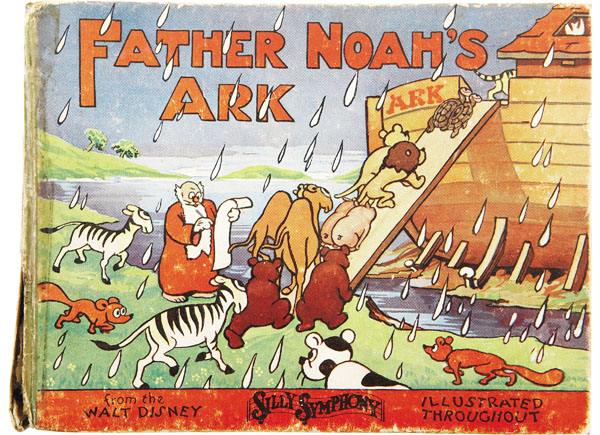

Father Noah’s Ark (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony, 4/8/33 Wilfred Jackson, dir.) – Undoubtedly the granddaddy of all Noah epics, far-distancing itself in complexity and spectacle from the prior primitive efforts of Paul Terry and Max Fleischer. The entire Noah family is introduced, including sons, their wives, and Mrs. Noah, who boasts of wearing the pants in this family. They are all already engaged in the construction and stocking of the ark, with the assist of animals of all kinds. (Porcupines, for example, form a continuous link nose to tail to provide a conveyor belt on which foodstuffs can be skewered on their quills and loaded post-haste through a side hatch in the ark. Rhinos slice planks from logs by charging them with their sharp horn. Hippos’ teeth provide neat nail holes in the ends of the planks, with woodpeckers driving in the nails. Snakes and giraffes act as cranes for hailing abard heavy equipment. Eventually, old man Sun takes on a distressed and worried face, as he is surrounded and blocked out of the picture by endless banks of dark clouds. The first lightning bolts light the sky, and the xylophone-accompanied first raindrops fall upon Noah’s blueprints. Noah and the boys sound a fanfare through ram’s horns to signal boarding time for the animals, who come a-running at the call. The line of arrivals at the gangplank is meticulously drawn, the Disney artists even taking time to distinguish lion from lioness. In a unique note of detail, Mrs. Noah supervises a second miniature gangplank, where all the world’s insects are being accounted for by her on a checklist. Noah has one holdout – a stubborn mule, who refuses to walk up the gangplank. (What happened to its mate?) Noah tugs and pushes to no avail, with only a lightning strike to the critter’s rear end being enough to get it to leap through the ark doors, cramming the conveyance to capacity.

Father Noah’s Ark (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony, 4/8/33 Wilfred Jackson, dir.) – Undoubtedly the granddaddy of all Noah epics, far-distancing itself in complexity and spectacle from the prior primitive efforts of Paul Terry and Max Fleischer. The entire Noah family is introduced, including sons, their wives, and Mrs. Noah, who boasts of wearing the pants in this family. They are all already engaged in the construction and stocking of the ark, with the assist of animals of all kinds. (Porcupines, for example, form a continuous link nose to tail to provide a conveyor belt on which foodstuffs can be skewered on their quills and loaded post-haste through a side hatch in the ark. Rhinos slice planks from logs by charging them with their sharp horn. Hippos’ teeth provide neat nail holes in the ends of the planks, with woodpeckers driving in the nails. Snakes and giraffes act as cranes for hailing abard heavy equipment. Eventually, old man Sun takes on a distressed and worried face, as he is surrounded and blocked out of the picture by endless banks of dark clouds. The first lightning bolts light the sky, and the xylophone-accompanied first raindrops fall upon Noah’s blueprints. Noah and the boys sound a fanfare through ram’s horns to signal boarding time for the animals, who come a-running at the call. The line of arrivals at the gangplank is meticulously drawn, the Disney artists even taking time to distinguish lion from lioness. In a unique note of detail, Mrs. Noah supervises a second miniature gangplank, where all the world’s insects are being accounted for by her on a checklist. Noah has one holdout – a stubborn mule, who refuses to walk up the gangplank. (What happened to its mate?) Noah tugs and pushes to no avail, with only a lightning strike to the critter’s rear end being enough to get it to leap through the ark doors, cramming the conveyance to capacity.

John Foster isn’t forgotten, as two skunks are the last to attempt to board. Noah and the boys react in horror, and pull in the gangplank, forcing the skunks to swim for it. No, thankfully, the skunks do not invade the ark’s cabins or chase anyone, but make the trip the hard way, being splashed and tossed around atop the ark’s roof, while the rest of the passengers remain safely inside. Did I say safely? Maybe not exactly, as the massive cross-currents of waves take a toll upon the animals, by tipping the interior cabins violently from one side to the other and back again, rolling the animals against the cabin wals like so many rubber balls. Surprisingly, outlandish sight gags are kept to a minimum during the storm, with only one lightning bolt sawing through the underside of a cloud to release the rain. Instead, most effort is concentrated on a well animated scene of waves passing at three different levels of depth from the camera’s view, with the ark helplessly bobbing around in the middle. Noah and family stay in a separate cabin of their own, praying and chanting on their knees to the Lord about the forty days of rain. As Noah repeats the chant, a leak in the roof briefly fills his mouth with water on the last note. He opens a porthole to spit the water out, but lets in a lightning bolt. He quickly runs to the opposite cabin wall, opening a second porthole to let the bolt out, then resumes his prayer. A forty-day hanging candle denotes the passage of time, until it is melted to its base. Outside, the Sun begins to return to view, and develops a broad smile as the skies clear to fully reveal him. The ship comes to rest on Mount Ararat, and a memorable and catchy original number, “The Skies are Clear”, climaxes the exceptional musical score. The skunks are the first down the gangplank, making way for the others. The others, however, have been busy during the trip, and in spite of the pitching decks, have somehow found the time to produce new families – particularly the rabbits, whose progeny parade in seemingly endless fashion. Last off the ark are the dogs, with both adults and pips taking no time to scout up the first trees revealed out of the flood waters, and cluster to sniff around their trunks, as the camera iris closes upon the image of the ark and the rainbow.

John Foster isn’t forgotten, as two skunks are the last to attempt to board. Noah and the boys react in horror, and pull in the gangplank, forcing the skunks to swim for it. No, thankfully, the skunks do not invade the ark’s cabins or chase anyone, but make the trip the hard way, being splashed and tossed around atop the ark’s roof, while the rest of the passengers remain safely inside. Did I say safely? Maybe not exactly, as the massive cross-currents of waves take a toll upon the animals, by tipping the interior cabins violently from one side to the other and back again, rolling the animals against the cabin wals like so many rubber balls. Surprisingly, outlandish sight gags are kept to a minimum during the storm, with only one lightning bolt sawing through the underside of a cloud to release the rain. Instead, most effort is concentrated on a well animated scene of waves passing at three different levels of depth from the camera’s view, with the ark helplessly bobbing around in the middle. Noah and family stay in a separate cabin of their own, praying and chanting on their knees to the Lord about the forty days of rain. As Noah repeats the chant, a leak in the roof briefly fills his mouth with water on the last note. He opens a porthole to spit the water out, but lets in a lightning bolt. He quickly runs to the opposite cabin wall, opening a second porthole to let the bolt out, then resumes his prayer. A forty-day hanging candle denotes the passage of time, until it is melted to its base. Outside, the Sun begins to return to view, and develops a broad smile as the skies clear to fully reveal him. The ship comes to rest on Mount Ararat, and a memorable and catchy original number, “The Skies are Clear”, climaxes the exceptional musical score. The skunks are the first down the gangplank, making way for the others. The others, however, have been busy during the trip, and in spite of the pitching decks, have somehow found the time to produce new families – particularly the rabbits, whose progeny parade in seemingly endless fashion. Last off the ark are the dogs, with both adults and pips taking no time to scout up the first trees revealed out of the flood waters, and cluster to sniff around their trunks, as the camera iris closes upon the image of the ark and the rainbow.

The Mail Pilot (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 5/13/33, David Hand, dir.) – Mickey, in charge of delivery of a valuable shipment of money via air mail, takes off in a small single-seat plane, despite reward posters at the mail station warning of the presence of air bandit Pete. This well-remembered aerial tale, also converted into a Big Little Book at the time of its release, features a short sequence of Mickey encountering various changes in climate along his aerial journey, prior to meeting up with Pete in a climactic battle in the sky. Mickey dodges lightning bolts which zip under the belly of his plane, skewer it in the tail, and flit into the path of his propeller blade (to be sawed up into dozens of little lightning bolts). When rain obscures the vision through Mickey’s flight goggles, he presses a button which activates twin windshield wipers, one for each eye. The storm grows colder, turning from rain to snow. A heavy coat of ice and sleet forms over the body of the plane, but Mickey gracefully soars low, following the slopes of the mountains below, until the storm is passed. As he emerges into sunshine, his plane shakes away its snowy coat, like a dog shaking water off of its fur. The sun musically reminds him that the mail must go through, and Mickey bids the sun a fond wave goodbye as he proceeds on his journey.

The Mail Pilot (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 5/13/33, David Hand, dir.) – Mickey, in charge of delivery of a valuable shipment of money via air mail, takes off in a small single-seat plane, despite reward posters at the mail station warning of the presence of air bandit Pete. This well-remembered aerial tale, also converted into a Big Little Book at the time of its release, features a short sequence of Mickey encountering various changes in climate along his aerial journey, prior to meeting up with Pete in a climactic battle in the sky. Mickey dodges lightning bolts which zip under the belly of his plane, skewer it in the tail, and flit into the path of his propeller blade (to be sawed up into dozens of little lightning bolts). When rain obscures the vision through Mickey’s flight goggles, he presses a button which activates twin windshield wipers, one for each eye. The storm grows colder, turning from rain to snow. A heavy coat of ice and sleet forms over the body of the plane, but Mickey gracefully soars low, following the slopes of the mountains below, until the storm is passed. As he emerges into sunshine, his plane shakes away its snowy coat, like a dog shaking water off of its fur. The sun musically reminds him that the mail must go through, and Mickey bids the sun a fond wave goodbye as he proceeds on his journey.

For a change-up, since we’ve shown the full cartoon in a previous post, I include here the rare pencil-test version of the flight sequence – one of the few pencil tests to survive from cartoons of this early vintage. Enjoy!

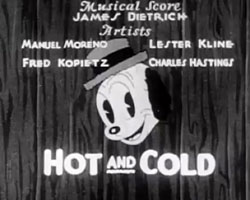

Hot and Cold (Lantz/Universal, Pooch the Pup, 8/14/33) – Pooch’s never ending wanderings with his bindle stick take him to the frozen north, where he meets a young Eskimo girl, plating fetch with her dog. (The dog may mark the first appearance of Elmer the Great Dane, considerably before his becoming a regular member of the Oswald cast.) Through a mishap, the dog falls partially into a hole in the ice, and becomes frozen in a large ice cube. The girl becomes panicked at what to do, but Pooch has the solution. Stepping to a nearby pay phone (with a ticklish rotary dial), Pooch telephone King Borealis of the North Pole, and musically asks him for a favor, to the tune of “Turn On the Heat”, a pop hit from the early Fox talkie, “Sunnyside Up”, starring Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell. The number was something of a natural for incorporation into a cartoon, as its original staging was nearly a live cartoon in itself. In the original film, a set full of arctic igloos is melted before out eyes, allowing the bevy of dancing girls to shed their furs and mukluks in favor of scanty chorine outfits. (Tragic that the color negatives for this sequence are lost.) King Borealis flips a switch on the wall, and the frozen land is bathed in instant heat, that not only thaws out Elmer, but turns the land into a budding springtime countryside. This does not sit well with a polar bear who is attempting hibernation, only to have his igloo melted away from around him. The bear angrily storms to the palace of King Borealis, intending to register a complaint, but finds the king cavorting in his court in celebration of the warm weather. Well, thinks the bear, it’s time to go over the royalty’s head – which he does by throwing a net over the King, tangling him up helplessly, and allowing the bear to reverse the wall switches, to bring back winter with a vengeance.

Hot and Cold (Lantz/Universal, Pooch the Pup, 8/14/33) – Pooch’s never ending wanderings with his bindle stick take him to the frozen north, where he meets a young Eskimo girl, plating fetch with her dog. (The dog may mark the first appearance of Elmer the Great Dane, considerably before his becoming a regular member of the Oswald cast.) Through a mishap, the dog falls partially into a hole in the ice, and becomes frozen in a large ice cube. The girl becomes panicked at what to do, but Pooch has the solution. Stepping to a nearby pay phone (with a ticklish rotary dial), Pooch telephone King Borealis of the North Pole, and musically asks him for a favor, to the tune of “Turn On the Heat”, a pop hit from the early Fox talkie, “Sunnyside Up”, starring Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell. The number was something of a natural for incorporation into a cartoon, as its original staging was nearly a live cartoon in itself. In the original film, a set full of arctic igloos is melted before out eyes, allowing the bevy of dancing girls to shed their furs and mukluks in favor of scanty chorine outfits. (Tragic that the color negatives for this sequence are lost.) King Borealis flips a switch on the wall, and the frozen land is bathed in instant heat, that not only thaws out Elmer, but turns the land into a budding springtime countryside. This does not sit well with a polar bear who is attempting hibernation, only to have his igloo melted away from around him. The bear angrily storms to the palace of King Borealis, intending to register a complaint, but finds the king cavorting in his court in celebration of the warm weather. Well, thinks the bear, it’s time to go over the royalty’s head – which he does by throwing a net over the King, tangling him up helplessly, and allowing the bear to reverse the wall switches, to bring back winter with a vengeance.

A big blowhard of a cloud begins blowing icy winds so fiercely, they rip the tops off mountain peaks. Penguins and Eskimos duck into an igloo (how come it’s not melted away?), but a walrus follows, forcing his way in, and popping out the roof, wearing the igloo like a skirt, and running off with it into the distance. A dog reaches into the window of an arctic barber shop, producing a bottle of hair tonic. He consumes the whole bottle – and his own short fur blooms into a fully tailored warm fur coat. As the storm continues to rage, the polar bear basks in the refreshingly brisk air – until Pooch arrives at the palace door to investigate. He spots the King tangled up in the net, and runs for the wall switches to attempt to shut down the storm. The bear intercepts him, tossing him out of the palace, and pursuing him over the landscape. Several other animals lend an assist to aid Pooch. Pelicans scoop snow up in their beaks, and drop it upon the bear in the form of a barrage of snowballs. Seals balance giant snowballs on their nose, tossing them at the bear, while a mountain goat butts the bear from behind, positioning the bear to take each blow directly on the noggin. A penguin breaks off icicles, and hurls them like javelins, forming a ring of them in the snow around the bear, like the bars of a prison cell. King Borealis is freed, and once again flips the switches, bringing on a summer that transforms both the palace and igloos into grass-thatched shacks from a South Sea island. As in the original Fox production, the Eskimo girls shed their fur coats, and become swaying Polynesian maidens. Inexplicably, the icicles do not melt around the polar bear, who remains imprisoned and profusely sweating. All ends happily, as Pooch and the Eskimo girl share kisses for the iris out.

A big blowhard of a cloud begins blowing icy winds so fiercely, they rip the tops off mountain peaks. Penguins and Eskimos duck into an igloo (how come it’s not melted away?), but a walrus follows, forcing his way in, and popping out the roof, wearing the igloo like a skirt, and running off with it into the distance. A dog reaches into the window of an arctic barber shop, producing a bottle of hair tonic. He consumes the whole bottle – and his own short fur blooms into a fully tailored warm fur coat. As the storm continues to rage, the polar bear basks in the refreshingly brisk air – until Pooch arrives at the palace door to investigate. He spots the King tangled up in the net, and runs for the wall switches to attempt to shut down the storm. The bear intercepts him, tossing him out of the palace, and pursuing him over the landscape. Several other animals lend an assist to aid Pooch. Pelicans scoop snow up in their beaks, and drop it upon the bear in the form of a barrage of snowballs. Seals balance giant snowballs on their nose, tossing them at the bear, while a mountain goat butts the bear from behind, positioning the bear to take each blow directly on the noggin. A penguin breaks off icicles, and hurls them like javelins, forming a ring of them in the snow around the bear, like the bars of a prison cell. King Borealis is freed, and once again flips the switches, bringing on a summer that transforms both the palace and igloos into grass-thatched shacks from a South Sea island. As in the original Fox production, the Eskimo girls shed their fur coats, and become swaying Polynesian maidens. Inexplicably, the icicles do not melt around the polar bear, who remains imprisoned and profusely sweating. All ends happily, as Pooch and the Eskimo girl share kisses for the iris out.

The Snow Man (Ted Eshbaugh’s Fantasies, 8/25/33) – This unusual, independently-produced cartoon, was notably sprung on the public, and later, upon home movie audiences by Official Films, without warning. It was billed theatrically under the harmless-sounding banner, “Ted Eshbaugh’s Fantasies”, and to the home movie audience in a family-friendly looking box with an image of a happy snowman resembling traditional images of Frosty. Even the opening minutes of the film look like traditional happy 30’s fare, featuring a young Eskimo boy cavorting with his arctic pals. Surprise! No one would have suspected that this film, in a heartbeat, would transform into a gothic horror story. The snow man, like Frosty, comes to life, but his facial features melt, transforming them into the image of a grotesque, raving monster, bent upon random destruction and devouring of those around him! Eshbaugh’s “Fantasies” are not for the faint-hearted.

The Snow Man (Ted Eshbaugh’s Fantasies, 8/25/33) – This unusual, independently-produced cartoon, was notably sprung on the public, and later, upon home movie audiences by Official Films, without warning. It was billed theatrically under the harmless-sounding banner, “Ted Eshbaugh’s Fantasies”, and to the home movie audience in a family-friendly looking box with an image of a happy snowman resembling traditional images of Frosty. Even the opening minutes of the film look like traditional happy 30’s fare, featuring a young Eskimo boy cavorting with his arctic pals. Surprise! No one would have suspected that this film, in a heartbeat, would transform into a gothic horror story. The snow man, like Frosty, comes to life, but his facial features melt, transforming them into the image of a grotesque, raving monster, bent upon random destruction and devouring of those around him! Eshbaugh’s “Fantasies” are not for the faint-hearted.

One may wonder if this idea was inspired by the box-office success the previous year of Paramount’s “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”, although there is no chemical potion, nor truly “good” side to the snow man, as he only looks harmless before he comes to life. There is also something strange about the gag writing and timing of the short, which is different from any other Eshbaugh product I’ve viewed. It begins with a dramatic sting from classical music which is closely associated with recurrent use at Warner Brothers following the departure of Harman and Ising, and also includes some gags that feel like they could have stepped out of a mid-30’s Looney Tune (such as an alarm clock ticking away calendar months instead of hours for a 6-month hibernation, accompanied by vocal ticking ending in the rhythm of “shave-and-a haircut”). But the classic Schlesinger animation staff hadn’t been assembled yet! So did anyone work on this cartoon who within a few years would be a regular member of Termite Terrace? If anyone has background data on the writers and artists who made this production, any clues to this mystery would be of great interest.

As mentioned, the boy and the animals construct a snow man, after awakening from their long hibernation, and begin dancing around it. Suddenly, they stop in their tracks, as the snow man’s hand begins to tremble and flex. The facial features of the snow creature melt into the image of a raging, snarling beast, and he develops his muscular skills to activate his arms and legs, becoming fully mobile. He lunges at the dancers around him, who scatter in all directions. Fish dive under the ice. Some animals pose one atop another as a totem pole, but are quickly found out by the beast. The snow monster begins tossing aside whole igloos in his pursuit of the animals. The boy, who is supposed to be our hero, at first appears to be a coward, leaping into his kayak out of harm’s way, and paddling furiously up an icy river rather than staying behind to save his pals. The beast manages to catch and swallow one of the fish, and also intrudes upon an arctic cathedral carved of ice, breaking up a prayer meeting, and also the church’s icy organ (at which the monster performs a self-composed solo before ripping out the keys, punctuated by an impersonation of Jimmy Durante’s “Hot-Cha-Cha”. He chases a flock of venison drinking by the riverside, uttering the over-acted line “Oh, dear, oh DEER”. Finally, he corners most of the cast at the edge of an ice floe, with nowhere to run. The boy, meanwhile, proves not to have been a coward after all, as he finally reaches the point of his intended destination – a hidden weather-control headquarters.

As mentioned, the boy and the animals construct a snow man, after awakening from their long hibernation, and begin dancing around it. Suddenly, they stop in their tracks, as the snow man’s hand begins to tremble and flex. The facial features of the snow creature melt into the image of a raging, snarling beast, and he develops his muscular skills to activate his arms and legs, becoming fully mobile. He lunges at the dancers around him, who scatter in all directions. Fish dive under the ice. Some animals pose one atop another as a totem pole, but are quickly found out by the beast. The snow monster begins tossing aside whole igloos in his pursuit of the animals. The boy, who is supposed to be our hero, at first appears to be a coward, leaping into his kayak out of harm’s way, and paddling furiously up an icy river rather than staying behind to save his pals. The beast manages to catch and swallow one of the fish, and also intrudes upon an arctic cathedral carved of ice, breaking up a prayer meeting, and also the church’s icy organ (at which the monster performs a self-composed solo before ripping out the keys, punctuated by an impersonation of Jimmy Durante’s “Hot-Cha-Cha”. He chases a flock of venison drinking by the riverside, uttering the over-acted line “Oh, dear, oh DEER”. Finally, he corners most of the cast at the edge of an ice floe, with nowhere to run. The boy, meanwhile, proves not to have been a coward after all, as he finally reaches the point of his intended destination – a hidden weather-control headquarters.

He enters a vaulted door, and a room containing a huge machine of meters, wheels, levers, and unknown fluids flowing through glass tubes. Pulling on a massive lever, he starts the mechanisms pumping and whirling. The beast has seized one of the animals in his hands, and is about to consume him, when the skies flash as if lit by lightning. The beast takes little notice as yet. Back at the weather station, the boy pulls the throttle wide open, putting the machinery into high gear. Suddenly, more flashes of double intensity light the sky, followed by a dazzling display of the Northern Lights from the horizon, utilizing rows of rays of every color Eshbaugh can draw out of the Cinecolor process. With these pulsing rays also apparently comes heat, as the snow man winces under the effects of their onslaught, and goes through a series of emphatic gestures that seem a combination of begging for mercy and defiantly shaking his fist at the forces of nature as if to say, “Curse you.” Suddenly, all is lost for the monster, as he rapidly melts away before our eyes, leaving a wide puddle on the ice where he stood. The boy exits the weather station and rejoins the cast, who note that there is something in the puddle left by the monster. The fish the beast had swallowed is alive and well from within him! The fish faces the camera, and replicates the evil laugh of the monster, as if to say, “So there”, as the camera irises out.

More action from 1933 and beyond, next time.